Data General

The Fair Bastards

It was the best of times, it was the worst of times

It's tough to describe my three years at Data General. On the one hand, DG and its founder Edson de Castro are responsible for almost all of my business success. It just would not have happened if Ed had not brought me east in 1976.

On the other hand DG did some really weird things. Some things were kookie and funny, but others were wrong and mean-spirited. As CEO, Ed is ultimately responsible for many of the things I experienced at DG -- both good and bad. But it's not easy to be critical. Forty years later I have come to know Ed in a different light -- far removed from the pressure and tension of business. He is a good person with many positive qualities. So, given the caveat that I consider my old boss to be a good friend, I will try my best to accurately describe my three important yet crazy years at his company. There's no way I could describe my life in the computer industry without including Data General, and there's no way to write about DG without mentioning the bad along with the good.

Culture Shock

I loved the Data General, but sometimes I hated it. Not hate -- that's too strong -- but I really disliked some of the things than went on. And I was confused. I had been suddenly thrown in to the real world, after seven years of insulation while at Hewlett Packard, the giant love-in.

I loved the freedom. I loved the fact that my boss left me alone — as long as I stayed within budget I could do almost anything. But there was a lingering feeling of distrust. I felt sometimes that I was not to be trusted — it was like some of us had ulterior motives. And the customers, the folks who buttered our bread — they were sometimes treated strangely, if not harshly. DG’s culture was an anathema to me — in many ways it didn’t pass the common sense test.

The company was a puzzle. It broke all the rules and yet was extremely successful. It had the reputation of being the "bad boy" of the computer industry -- heck, of any industry. And it enjoyed this reputation. DG became a public company less than two years after it was founded and shattered records in making it to the Fortune 500. Too bad Harvard never wrote a case study. It would have been groundbreaking! But if they did Harvard would have had to admit that EVERYTHING they taught about how to run a business could be wrong…

I was given very few orders from my boss. Just get the job done. I loved reporting directly to the president of the company — Edson de Castro, The Captain. The founder of what by 1976 had become one of the most exciting and successful computer companies in the world. Although I had a great job at Hewlett Packard I was way down the totem pole at that huge company. At DG I was close to the top. Close to being a star!!

At HP you felt secure, no matter how bad you screwed up. It would have taken an act of bloody murder to get fired. The contrast with DG was extreme. Employees were kept on edge. Your job was simple: help the company make a profit — that’s why you’re here. We were all given a lot of rope. But if you screwed up just take that rope and hang yourself before someone does it to you. It was clear that everyone was expendable.

Stockholders were put on a pedestal. Keep them happy. How? Profit. Everyone at DG knew the company was driven by profit — at all costs. This was new and different to me — at HP people hardly knew how to spell profit. DG was totally counter to the “HP way” — they were as different from Hewlett Packard as a cow is to an orange.

Ok, I loved the place and I disliked a few things. So what? The net result was very, very positive. In fact, it was life changing. Ed brought me from Silicon Valley to sweet New England, out of la-la land and into the real world. DG helped to make me tough. I was a cream puff at HP — I never could have started Stratus straight out of that company. Joining Ed’s company put me on the path to becoming an entrepreneur.

My first day at DG was right after Halloween, 1976. I remember it well. Marian and I had gone to a costume party at our friend’s houseboat at Jack London Square in Oakland. The party was fun as usual but I knew this was my last day in California — the next morning I would be leaving my family behind, getting on a plane for Massachusetts. I hated the thought of leaving them for the next two months. The plan was to let our three small kids finish their semester at school before the whole family moved out in January.

All five of us were natives of California. Nobody left that enormous state back then — everyone was trying to get to the Left Coast. Our family and friends thought we were crazy.

My title at DG was Director of Software Development, reporting directly to Ed. All of his other direct reports had the Vice President title. Oh well, maybe one day I would be a VP…

Right away I discovered that software was not at the top of the food chain. My people didn’t work in headquarters with everyone else. Instead they were exiled a few miles down the road to an abandoned shopping center. They shared a building with the cable-cutting operation. The programmers created software while listening to the constant CHUNK, CLUNK, CLANK of the cable-cutting machines. I learned that the previous year there was talk of moving software all the way up to Maine. A crazy idea — luckily it fell through.

For you non-computer people you need to understand that separating the software people from the engineers who design the hardware was very wrong. Software is the heart of a computer. A computer is useless without the basic stuff that my people developed: the operating system, programming languages, data management software, communications, etc. But DG didn’t see it that way. Its roots were hardware. Software was a necessary evil, created by hippy-freaks.

But in spite of the less-than-satisfactory working conditions the people were great. DG had attracted a bunch of top notch software engineers -- equal to if not better than the ones at HP. I was used to the shiny new buildings that HP had built in the middle of some Santa Clara Valley orchards. I took me a while to figure out that if the programmers loved the company and the people that they worked with, the building didn't matter --even if it was an old supermarket.

DG was 8 years old when I joined. It had spun out of Digital Equipment Corporation in 1968. Ed was a young engineer at DEC and tried to convince its founder Ken Olsen to drop the 12-bit line in favor of 16-bits. In fact, he had a design for the new computer. For some reason Olsen wasn't interested. So Ed and two others took the design and started Data General. Olsen didn’t sue — it wasn’t his style. But years later he was quoted in Fortune Magazine saying “What they did to us was so bad we’re still upset about it.” I’m mad as hell but I’m not going to do anything about it. Not surprisingly, Ed was always a little paranoid about anyone spinning out of DG and starting another computer company.

Ed is on the left. Herb is the good looking guy on the right :)

At its beginning in ’68 DG was essentially selling "naked" boxes with minimal software to highly skilled engineers. But by the time I joined a lot of their new business was in the commercial world, where their customers depended heavily on software that my folks developed. But DG still had the box mentality. Software was not part of their culture. This sometimes created big problems as DG entered the commercial marketplace.

In the year that I joined, 1976, Data General was flying high — one of the hottest companies in America and the clear number two in minicomputers, right behind DEC. Excellent financials. I didn’t know much about them while at HP — we didn’t cross paths much. I do remember being at a trade show in Las Vegas where DG posters hawking their products could be seen everywhere — at the airport, taxicabs, buses, all over the convention hall. It was very unusual for a tech company to be that much in your face. At another trade show in New York I saw a big crowd around the DG booth. I elbowed my way to the front and there was a belly dancer with a micro-Nova chip in her navel. A very bold thing for the stodgy computer industry. DG’s booth was the hit of the convention.

During my first week my head was spinning. What’s going on? I felt like Alice in Wonderland — everything was upside down and backwards. Or maybe I was the weird one and what I was seeing was normal....

One of my guys told me that DG was about to ship a newly developed disk drive, but my programmers had never seen one — they had never been able to check out their “drivers”, the software that controlled it. There was a great chance that it wouldn’t work — but when I called Paul Stein, the manufacturing VP, and asked him to stop shipments he told me “Forget it. The disks are going out the door. I need them to make my profit goal for this quarter.” Apparently Stein felt profit trumped shipping things that worked. Once it’s off the loading dock and in the truck we could log the revenue and satisfy the stockholders. And Paul would make his goal. Fix it later.

One of my people had his car squashed in the parking lot. DG was expanding the building and during construction a front-end loader rolled over the poor guy’s car. The kid always came to work at 6am so his car was parked in the front row. DG refused to cover his deductible. Jim Campbell, our VP of Personnel told me, “sorry Bill, it’s against policy. It's between him and his insurance company…” I organized a fund and we all quickly chipped in the $500 that the kid needed. This was really silly -- DG missed a golden opportunity to creat tremendous good will with their people.

At Hewlett Packard it seemed like we were always writing things down -- producing tons of plans, most worthless. A waste of time. DG had the opposite mentally -- don't put too much stuff in writing. It might get into the wrong hands. Our arch-enemy DEC might steal our secrets. At Data General secrecy was a highly valued commodity.

One morning I was accosted by a couple of burly security guards as I mistakenly tried to enter through a side door at headquarters in Southboro. Remember the movie The Firm? The chief of security was played by Wilford Brimley. Big, tough, no nonsense, walkie talkie glued to his hand. Looking back that’s what one of the guys looked like — a spitting image of Wilford Brimley. He demanded my ID. I was held there while he called it in, making sure I was who I said I was and not a spy from DEC.

While in the cafeteria line I watched Herb Richman, a co-founder and VP of Sales, take a bite out of a customer’s sandwich and then put it back on his tray. Cracked me up.

Herb was a character -- a salesman's salesman. Fun loving but tough. He had created one of the best sales forces in the industry. A few years later when Bob Freiburghouse and I had teamed up to start Stratus Bob said "let's hire DG salesmen. They are the best in the industry." He knew -- Bob worked with DEC, Prime, and Wang as well as DG and he saw the differences.

I watched Herb’s Mercedes being towed away from visitor parking in front of our building one morning. Ed had his co-founder’s car towed because no employee was allowed to park there, not even Herb. I saw this towing thing happen several times over my three years. I wondered if it was really a set-up between Herb and Ed — to show everyone that at DG nobody got special treatment. But a good friend who knows both of them very well said he is certain it was real. Herb was constantly trying to pull something over on Ed but he could never get away with it — Ed was just too smart. And just because Herb helped found the company he wasn't ever going to get any special treatment.

I learned right away there was almost no management structure for my 140-person software group. Programmers pretty much roamed around, doing whatever they wanted, with almost no accountability. For example, there were three projects working on three different versions of a Basic Interpreter. We only needed one. Meanwhile other software products that we needed badly weren’t being done. Management by Brownian Motion. This is why they hired me -- Ed knew that the software department was out of control.

My first evening on the job Ed hosted a dinner party at the local Sheraton so that I could meet the “managers”. It turned out he and the personnel guy had to guess at who to invite because the software group had no formal structure. Several people were invited who definitely were not managers and some real managers were passed over. This pissed off a lot of people -- one of my first jobs was to calm them down.

One morning Jacob Frank, the company’s chief lawyer walked in to my office with a document.

“Bill, you need to sign this.”

“What is it?”

“Your employment agreement. Everyone who reports to Ed has to sign.” I quickly read it. The document said that everything I did or even thought about while working at Data General belonged to them. EVERYTHING, whether it had to do with computers or not, and for ONE YEAR after I left!! They owned me and my thoughts now and into the future!!! I’d already burned all my bridges to HP. There was no turning back. I had to sign. What I didn't realize then was that non-compete agreements were not uncommon at the higher levels of businesses. In my naivete I figured they were pulling a fast one on me, because nothing like this existed at HP.

This little piece of paper would haunt me for years to come. It made me feel like my skinny neck was glued to the chopping block with an ax hovering just above, ready to slice. The agreement almost prevented me from quitting and pursuing my Big Idea. Later, just as Stratus’ venture capital deal was about to close, our investors discovered this agreement and nearly backed out. In 1981 I lied to Harvard when they wrote their case study about Stratus because even though I had left DG more than two years earlier my ex-employer and this agreement still worried me.

In the middle of the night during my first week I was jolted awake with an epiphany!! I know what’s going on — this isn’t real — it’s a test! Kind of like Candid Camera — someone created a totally crazy scenario. If I survive I'll become President of Data General!!! That must be what’s going on — it’s just a big, elaborate, test… If I pass I will run the entire company!!

When I came back down to earth depression set in big time. Had I made the biggest mistake of my life? HP would not take me back. We had sold our house in California. We were committed. There was no turning back.

I needed a break. A diversion. I needed to relax. I decided to go to the movies. There was something called The Marathon Man playing nearby. It had a good cast: Dustin Hoffman, Laurence Olivier, Roy Scheider. How could I go wrong?

Let me tell you, if you ever want to chill out with a relaxing movie, never, EVER watch The Marathon Man. It is one of the tensest movies imaginable, especially if you're already frazzled like I was. When Laurence Olivier used a dentist drill to dig into a nerve in Dustin Hoffman’s tooth, softly saying “is it safe?” while Hoffman screamed bloody murder, I bolted from the theater. I couldn't stand it. The worst possible movie that I could have picked at that time.

My first priority was to put together some kind of structure for the 140 people who worked for me. For the first month I spent most of my time organizing the group. Getting to know everyone. Searching for some leaders. I found a few good ones within software and managed to convince a couple of others from different parts of the company to join me. Finally I was ready to present my new organization to Ed’s staff. It was pretty standard for software development in a computer company: operating systems, languages, communications, user manuals, and FHP — DG’s new super secret computer system.

After the meeting Ed pulled me aside. “Don’t mention FHP around Herb.” The soft spoken guy almost raised his voice!

“How come? He’s on your staff and he’s a founder of the company.”

“Herb will leak it. He’ll sell it. Don’t talk about FHP in front of Herb.”

Hmmm. The most important project DG was working on — the future of the company. And Herb, one of the founders, was supposed to be kept in the dark. I began to realize Ed had a fairly unusual relationship with the sales guy that helped him start DG.

In the early 80's, after I had left DG, group of sales guys started a band to chronicle the culture of this wacky company. Check out the song by The Talkingpropellerheads about Ed and Herb, with Dan Fennelly leading the group. Ed's wife Eileen was an occasional member of the band -- that shows how tolerant Ed was of much of the fun stuff that went on. The guy that ultimately replaced Ed killed the band....

Edson was an enigma, just like his company. He was (is) a brilliant person. He flies his own jet and could probably take the whole thing apart and put it back together again, blindfolded. One day I saw him pouring over the schematics for some complex piece of electronics. He had just added some new avionics to his Beechcraft Baron and wanted to completely understand the design.

He was a shy person. One-on-one conversations could be awkward. Oftentimes in his office when we were discussing something and then the conversation finished he would just stop talking and look down at his Wall Street Journal, which was always open on his desk. No “I’ll see you later” or “have a good day” or any conventional closure. Just silence. I would stumble backwards out of his office, trying to avoid falling on my ass.

Maybe it was the work environment that made him reticent to make small talk with his employees. Maybe he didn't believe in it. I know from experience it is very hard to be good friends your people, and then have to take harsh action like demoting or firing. I think in hindsight Ed kept his distance from his people for good reason.

Ed is very soft spoken. I’ve never heard him raise his voice, no matter how angry. He could whisper “that’s bullshit” in the softest possible voice but somehow the words penetrated down to your bones. But put him in front of a large group and he was dynamite. At annual meetings or sales events — anything with a big crowd, he was great. Always in command of the facts, a superb public speaker.

There were two classes of people at DG: the Insiders and the Outsiders. Ed, Herb, and Jim Campbell were the insiders. Jim was the VP of Personnel, and an old high school friend of Herb’s . Everyone else felt like an Outsider. We were not part of the inner circle, and were always a little on edge.

It was very odd that Herb, a co-founder, had very little authority. On paper he ran sales and marketing but in practice it seemed like he couldn’t sign for a cup of coffee. Many mornings I would see him camped out in front of Ed’s office, waiting for the magic time of 10:30, waiting for The Captain to arrive, waiting to get authorization for whatever. Something must have happened before my time to cause Ed to strip Herb of all power.

The World’s Best Computer

Back to FHP — Fountainhead Project. DG’s new, SUPER SECRET computer. So secret they rented rooms miles away from headquarters in the Fountainhead Apartments so that the hardware and software guys who worked on it wouldn’t mingle with the rest of the company. Keep them away from mainstream DG. Keep them away from Herb. Keep them away from spies.

A fellow by the name of Bill S. ran my part of the project — the software part. The hardest part. At first glance Bill seemed like a capable enough person. Smart, witty, seemed to say all the right things. I asked him to tell me about FHP. Describe the product, the computer’s architecture. Bill said “I could do it but the best person would be Jerry. Talk to him.”

I found Jerry. He suggested I talk to Lem — “Lem is a great communicator and has a super presentation on FHP.” I tracked down Lem.

“Bill, the world’s best describer of FHP is George. While I could tell you about it, George would do a much better job.”

I began to smell a rat. This project has been underway for more than a year and I was getting the runaround. George finally sat me down in front of a black board and starting drawing. He didn’t have anything in writing (big surprise) — he just put up a bunch of things on the board. The “exciting” thing was what they called a “soft” architecture. This meant that the instruction set was not fixed — the machine would swap instructions in and out depending on what language the application was written in. One set for Cobol, another for Fortran, etc. There was also a plan to imbed much of the OS in microcode. The rest of FHP was pretty standard: multi-tasking, virtual memory, maybe multi-processing.

Variable instruction set? Burroughs tried that and it bombed. Way too complex, and switching between instruction sets was very slow.

Embed the OS in microcode? That sounded really tough, really risky. I asked George what the goals were for FHP? What were the design objectives? “No goals in particular. Just build the world’s best computer.”

“When will we be shipping?”

“Haven’t figured that out yet — probably in two or three years”

I left the building even more depressed that ever. Comically, I couldn’t help but notice that FHP had taken over several ground floor apartments at Fountainhead. Everything George drew on the blackboard was facing the parking lot. Anyone could easily look through the windows to see DG’s plans.

Now, this gets to my biggest failing at DG. I should have tried hard to kill the project right then and there. There was no frigging way that FHP as described was ever going to see the light of day. Telling a bunch of engineers to “build the world’s best computer” was crazy. Computer geeks need limits, boundaries, deadlines. Otherwise the project gets hopelessly complex and nothing gets out the door. Keep it simple, stupid.

I didn’t have the power to kill FHP but at least I didn’t just sit on my thumbs. I immediately wrote Ed a memo — about 15 pages. I put my heart and soul in to it. It meant so much to me that I still have a copy, four decades later. The first 10 pages were pretty general stuff under the heading “A newcomer’s View of DG.” For example, we needed to always test software on new hardware before it shipped.

The last five pages focused totally on FHP. HP taught me that long, complex computer projects always fail. I told Ed we should drop the “soft” architecture — it was way way too complex and risky. Instead, there should be one small, simple instruction set. FHP should be a 32-bit mid-range product, not a big, expensive main-frame. We needed a replacement for our 16-bit Eclipse.

Sadly, my memo had no effect. Nothing changed. FHP continued down a path towards oblivion. An enormous waste of money. Not being able to either kill or drastically change FHP was my biggest failing at DG. I suppose I could have been more forceful, but I wasn't. My bad.

Gonzo

DG hired several new VP’s between 1975 and 1976. Business was growing fast and they needed to beef up management. While HP nearly always promoted from within, Data General looked outside to fill most important jobs. I benefited from both sides of that equation. At HP I was promoted to run the computer development group while I was still very wet behind the ears. And DG rarely looked inside to fill big positions. I don't know how many candidates they went through for my job but I know I wasn’t their first choice.

DG hired Dick Weber from Honeywell to run U.S. Sales. Back in the ’70’s Honeywell was one of many companies in the computer business — one of many that are now defunct. I really liked Dick. He was smart, very capable, a real straight arrow. I went on numerous sales calls with him, always had a good time and learned a lot about selling. I was an engineering geek and figured it couldn't hurt to learn how to sell.

One day Herb stuck his head into my office. “Hey Bill, how’s it going?”

“What’s up Herb?”

“Ed is firing Weber right now. I know you like Dick and I wanted to make sure you don’t freak out.”

This was crazy. Dick was one of the good guys. And US sales were booming.

“Why is Dick being fired?”

“He doesn’t fit in. We don’t like him. But I want you to know that you do fit in. We do like you.”

Gee Herb, thanks. It's nice to know that I fit in. My thoughts -- I didn't have the guts to say it. I never learned exactly why Weber was canned. But this episode really put me on edge for the rest of my time at DG.

Three years later I tried to recruit Dick to join me as a co-founder of Stratus — to run sales and marketing. Dick wasn’t going for it. He was a big company guy — he had returned to Honeywell. No interest in hanging out with a bunch of engineers in a dumpy old building. Oh well. He would have been good. But we lucked out and eventually got a much better guy from Honeywell — a little man in a green rumpled suit who years later went on to run and grow Cisco, one of the computer industry's iconic companies.

Having an office next to Herb’s was always a ball of laughs. Once when I was interviewing a techie from MIT Herb suddenly walked in with the latest issue of Playboy. Sticking the centerfold in my face he said, “Hey Bill, what do you think of those???” The MIT geek turned beat red and mumbled something about going up the road to DEC.

Customer Dissatisfaction

I was still brand new at DG when Ed asked me to come with him to Chicago the next day. “We’re going to visit Hyster. They’re really pissed off. Tom is coming with us.” That would be Tom Cook, our VP of Customer Service. Tom had recently joined from IBM. He was a another really good guy. Really knew his stuff. If a customer visit involved Tom they must have been very upset.

I knew of Hyster, the fork lift company. At the tail end of my HP days we were fiercely competing with DG for the Hyster account. DG won and we were devastated.

We walked into the Hyster board room. The chairman and about 10 of his VP’s were there. The chairman proceeded to tell us how crappy our product was. The computers kept crashing — and a some of the promised software hadn’t been delivered. “What are you going to do about it?”

Ed spoke softly: “I know that you’re upset. But you have to realize these are computers. There are always problems. Especially with the software. That’s why I brought Foster. He will get that stuff working. But meanwhile, you’re not living up to your volume purchase agreement. We gave you a big discount, and we expect you to take all the Novas that you agreed to buy.” My jaw dropped. Tom Cook’s jaw dropped. We could’t believe what our boss just said.

The Hyster guys couldn’t believe it either. “You mean you want us to keep taking that crap even though it doesn't work?? Really?? Please leave the room, we need to talk in private.”

In the hallway outside I wanted to ring Ed’s neck. I wanted to shout “YOU JUST PISSED OFF A CUSTOMER!!! NOT JUST ANY CUSTOMER, BUT AN EXTREMELY IMPORTANT ONE!!!” But I didn’t say say a thing. I was still in shock, and besides, I wanted to keep my job.

Ed spoke: “I really love to pull their chains.” He was having fun!! Ed thought that pissing off a customer was cool! Tom and I were flabbergasted. It wasn’t because we were from IBM and HP — customer friendly companies. NO company in its right mind would do what Ed just did!

Ed knew that Hyster was pretty much locked in to our stuff — they had invested lots of money in software that would only run on DG computers. So maybe that’s why he didn’t care. No matter, it still didn’t make any sense. We eventually fixed the problems and Hyster was satisfied. But the next time they needed to develop a new computer system do you think they chose DG?

I’ve seen Ed many times since we both left DG. I’ve had plenty of opportunities to ask him about that crazy Hyster trip, but I never have. I guess I’m still a little intimidated by him. Maybe that’s natural — your old boss is still your boss, even 40 years later….

Ed normally started work late, around 10:30. But there was one time that I remember him coming in early. One morning sitting at my desk I was startled to see Ed walk by. It was only 8:30! What’s going on! Then I remembered the strange flag flying on the pole next to Old Glory. Turns out it was the North Carolina state flag. Their governor was visiting. Ed came in early to greet him!! Ed was in the process of sticking it to Massachusetts and its liberal, anti-business attitude, and was starting a division in North Carolina. Those guys were tickled pink to be taking some jobs away from Massachusetts.

Ed treated himself like everyone else —no special perks for The Captain. By the time he got to work each morning our big parking lot was filled — Ed parked in the back about a mile away…

One cool thing about DG was stock options. We didn’t have them at HP. I had never heard of them. When I hired on I was given a few thousand options. Here’s an example of how they work. Let’s say you are granted 100 options today, at today’s stock price. But the kicker is that you can buy these shares at some point down the road —maybe as long as five years from now — but, at today’s price. So, if the stock is trading for 10 bucks today, but 5 years from now it’s at $50, you can “exercise” the option of buying shares at the $10 price!! Then you can sell the shares for $50. A cool 40 bucks per share profit. A really smart concept — everyone wins, no one loses. It motivates people to get the stock price up. Shareholders like that. But if the stock price stays the same or even goes down nothing happens — no one gets hurt. You would not pay $10 for a stock that you could buy on the market for $5.

It’s amazing how the press always screws up the reporting of options. As an example, suppose when I was CEO of Stratus I was granted by the board 100 options at today’s price of $10 each. The press would say, “Bill Foster, CEO of Stratus, was just given $1,000 in Stratus stock.” That’s total bs. I wasn’t given anything of any value — when first granted options are worthless — they only have value if the stock price goes up. I don’t know if members of the press are just stupid or it’s their liberal bent that makes them want to trash management. Options are consistently misreported by the press.

Soon after I was hired Ed told me, “Bill, I could give you your options now. But I think our stock is overpriced. If you want you can wait to see if it goes lower — then you can have your option. Your call, just tell me when you want the option.” That was really cool. And smart. As far as I know it didn’t break any rules.

Another thing that was totally new to me was DG’s Million Dollar Club. They held their first one soon after I joined, in the spring of 1977 — in Bermuda at the Sonesta Resort. Anyone who sold a million bucks of computers got to go. It turns out that these types of sales clubs were pretty common in the computer industry. Almost everyone had them — except stodgy old HP.

The 60’s and 70's were the pinnacle years for the computer industry. Business was booming. Gross margins for hardware were 80% or higher. That means that if a company had $100 million in annual sales it would have $80 million left over after the computers were built and shipped!! $80,000,000 to cover engineering costs, sales, marketing, and overhead. And there should have been a bunch left over for profit. Because of these huge margins computer companies had plenty to spend on ridiculous trips and prizes for their pampered sales people.

At DG’s first club there were about 20 salesmen — they were all men. Ed invited me and a few other “executives” to come along, so that the sales "winners" could rub shoulders with us and feel even more special. This was great — I loved it, I had never been to Bermuda, it was a free vacation — what’s not to like? The only negative was we had to share rooms. My roommate was Paul Stein, the manufacturing VP. Paul had recently come over from Burroughs. He was an ok guy but not exactly a ball of fun — pretty much all business all the time. Plus he snored to high heaven, but maybe I did too, who knows?? Who am I to complain? In the early days of Stratus we doubled up all the time. At the Red Roof no less!!

The highlight of the event was Herb’s closing speech to the troops. Herb was funny, witty, amusing — as usual. Lot’s of laughs. It turns out at the same time we were there IBM was having it’s Golden Circle event at the South Hampton Princes just a mile or so away. They had taken over the ENTIRE large hotel. Wives were included. Henry Kissinger was the guest speaker. Harry Belafonte for entertainment. We at little Data General had Herb for both. But he was great. Herb ended his talk to the sales team with this: “I’ve been telling you guys all along to screw IBM. But if you can’t do that then go down the road and screw their wives!!!!” Typical Herb. He broke the place up.

Conventional wisdom is that the engineers are the really smart ones in computer companies. But I’ve decided it’s really the guys in sales. They somehow convince everyone that to do their jobs right they needed special incentives: Winner’s Circles, Million Dollar Clubs, Golden Circles, free trips, free stuff, awards, plaques, pats on the back. And huge commissions, especially if they beat their quotas. What do engineers get for doing their jobs? Or folks in manufacturing? Or accounting? YOU GET TO KEEP GETTING YOUR PAYCHECK!!! Come on, engineers, dummy up! The sales guys are laughing all the way to the bank. And to Bermuda.

In early 1977 we moved into our new corporate headquarters in Westboro. The new digs were a big improvement, and included an executive row. All the VP’s and Ed sat in a row of big offices at the front of the building. Behind a glass door. No one could accidentally walk past an important person’s office — it took a special, concerted effort to enter executive row.

I was the only non-VP there — I was only a Director. When I went to see the facilities guy about my new office he looked at me like I had two heads. “What makes you think you’re getting an office up there? You’re not a VP!”

“Ed told me I could have one.”

“Really? Are you sure?? I’ll call him.” For the first few days at DG I thought I was a big deal, but quickly I learned I was just another pogue. This was another example of pushing me back down to earth. The facilities guy, Dom, spoke to Ed in a hushed tone and then turned to me. “Ok, I guess you’re right. I’ll get you an office up there.” Gee, thanks -- thanks for admitting that I DIDN'T LIE TO YOU!!! Oh, the ignominy of it all!! More proof that I was of no importance!

At least with this office I wouldn't look like a second class citizen in front of my troops by not being on Executive Row with the Big Boys. And our large offices were really cool! Dom assigned me to an office right next to Herb Richman. This had to me one of the most entertaining spots at headquarters.

Now that we were in the new building my guys no longer had to work in a run-down shopping center along with the cable cutting operation. But they were located about a mile from my office — at least it seemed that far. Software was placed downstairs at the back of our enormous building. They were as far from me as they possibly could be. But I would not give up my office in executive row. I felt important up there. I did, however, sneak in a secret desk right in the middle of software so that it was easier to hang with my people.

Foolish Programmers

One morning Jim Campbell rushed into my office, grabbed the Data General Mini News out of my in-box, and as he left he said “Bill, you need to get control of your people!” What’s going on? I hadn’t yet read the latest issue of our company newsletter.

I should have guessed. It was April Fool’s Day, and some of “my people” had come out with their own edition of the Mini News. Campbell was scurrying around trying to grab them all up. I called down to Matt Blanton, one of my guys, and told him to hide his copy. I still have that newsletter.

It was a was pretty benign joke — not too horrible, in my opinion. Jim should have just left it alone. Maybe he was worried about the announcement of a $5,000 cash bonus for referring new hires. There was no such program.

Or the article about the town of Westboro voting to move their town line to the west so that DG would no longer be part of the town — this was actually pretty funny. The article mentioned that Westboro didn’t want to process all sewage that we were producing, and that Southboro, on the other side, had already moved their town line further east so that DG headquarters would no longer be in any township in Massachusetts. A man without a country... This article was immediately followed with the headline “Need Fertilizer?” DG suddenly had a surplus of unprocessed organic fertilizer which anyone could pick up for free. To top it off it was being packaged by Servamation, the people who ran our cafeteria.

Another article entitled “Muskrat Love” mentioned that we were being sued by the Captain and Tennille for $1 million because of the constant sounds of muskrats in our phone system. At the end of the article there was this: “Caution!!!! Turn down your telephone buzzer — muskrat mating season is about to begin!!!”

Another headline: “VP Takes Leave” “Herb Richman, comedian and part-time DG Vice President, will take a two-year leave of absence beginning next week to join the Kansas City Bombers roller derby team.”

The newsletter ended by reminding everyone that since April 2 was John Galt’s birthday it was a paid DG holiday and everyone could sleep in. There were some pretty funny folks at Data General. And of course since Jim was trying to destroy the fake newsletter everyone devoured every word.

More Humor

The new headquarters building finally placed software next to hardware, which was a good thing. Software and hardware are integral to a computer system. It was kind of hard for the software guys to do their job when the guys who developed the hardware were in the next town.

But being co-located did cause some problems. Just like at HP, the DG software guys were a little weird — a little off-kilter. The hardware guys were pretty normal, as far as geeks go. Late one evening I got a call from Tom West, DG’s top hardware guy. He sounded angry. “Bill, I was walking through software on my way to the parking lot and I got hit in the head with a frisbee!! What the F!!!” I went down to investigate. Turns out there was a good reason: The guy who threw the frisbee was riding a unicycle through the halls. The next day I told Tom I would not let them toss the frisbees "whilst ridding unicycles." He wasn’t amused.

Washing Machine or Disk Drive?

Back in those days some computer disk drives looked like washing machines. About the same size, with a removable stack of 15-inch disks inside. The idea was that when you filled up the stack you could remove it and drop in a new one. The disks had a big, maybe 5 inch hole in the middle. One of our guys thought it made a perfect hat. Dan would walk around the building with the disk on his head, with his ample thick, curly hair poking through. No one gave it a second thought.

These washing machine drives had a quality problem — the lids on top kept randomly popping open causing the computer to crash. One day I walked into the lab and saw a heavy construction brick on the top of the disk drive holding the lid down. The brick was painted in the official DG blue color, with a DG logo pasted on the side. The construction brick looked like an official part of the DG product line.

Matt Blanton, one of the guys that I recruited to help run software, called me early one morning. “b-b-Bill, I’ve decided to f-fire Dan but he’s here in my office with a t-t-tape recorder.” Matt, the nicest guy in the world, was a little upset. He was thrown off kilter by the tape recorder, and this briefly affected his speech.

I told him “don’t worry about it, just fire Dan if that’s what you want to do. If he decides to sue us we have an army of lawyers — with plenty of experience.”

I had started to get used to this firing thing. At HP we never fired anyone. It would have been impossible to fire someone and besides, that would be against The HP Way. I’m sure Matt had a good reason for getting rid of Dan, but I didn’t ask — I trusted Matt’s judgement. Dan probably screwed up one too many projects.

In the summer of 1977 I fired Bill S., the leader of the super secret FHP project. He was screwing up everything, missing every schedule, way over budget. The more I got to know him the more I learned that he was just a giant b.s. artist. (Hence, his initials?) Almost everything he said was crap. Sounded good at first, but was always crap. The final straw was a trip he took to a trade show. Bill had been twisting my arm and insisting it was vital for him to go, to see what the competition was doing. He never showed up at the show, and spent the entire time visiting old friends in San Francisco. I was looking for a reason to get rid of Bill and finally had one.

It all happened quickly. At the end of the day I called him in to my office — I told Bill he was fired. He didn’t protest — he had sensed for awhile that he was on thin ice. Security escorted him out the side door, straight to his car. He was gone. Everyone in software pretty much knew that when Bill S. didn’t return to his desk he was gonzo.

The very next week I needed to talk to one of my guys, Jit Saxena— one of our best people. It was late in the day. When we finished our conversation Jit figured rather than making the long trek back through software he would just go out the side door straight to his car — he never returned to his desk. Everyone figured I fired him. When he told me the next morning about all the calls he got that night consoling him for the loss of his job, we had a big laugh. A big, nervous laugh, because at DG this could happen to anyone. At any time.

Best Mission Statement Ever

In 1978 Fortune magazine wrote an article about DEC and DG. Mostly about the animosity between the companies. It talked about how Ken Olsen thought the Nova rightfully belonged to him because Ed designed it while at DEC. But the highlight of the story was Herb Richman’s quote when he was asked about DG’s tough reputation. Herb said, “Sure we’re bastards. But we’re fair bastards.” The best possible elevator pitch to describe Data General!

At a staff meeting it was mentioned that Apple promised to take all of their employees to Hawaii if they made their sales goal. Apple was new, booming, and still a private company. I blurted out “we should have a similar program. A really big sales goal — a real stretch. If we make it we could charter a bunch of 747’s and take everyone to Hawaii. We could drag banners behind the jets that say “THE FAIR BASTARDS.” I thought this was pretty funny. Nobody else in the room laughed. I guess I was starting to feel a little more secure to even come out with such blasphemy.

WSJ November 1975

Fast forward a year later. One day in a staff meeting there was talk about a DG competitor in New Jersey that was making knock-off Novas — Digital Computer Controls. DG sued DCC the previous year for stealing their design. Now we were going to buy the company and give its CEO really tough if not impossible sales goals, so that he would never get his earn-out.

WSJ January 1975

This reminded me of an old story that had circulated the industry. It was rumored a few years earlier that DG had burned down a west coast company because they were duplicating DG parts. Keronix filed suit, accusing Data General, Ed de Castro, and Fred Adler of having their building set on fire and while they were at it wiretapping their phones. I was vaguely aware of this caper but didn’t pay any attention — I was still at HP. Keronix was unable to prove their allegation and eventually dropped the lawsuit. But maybe they did deserve to be torched. Keronix had stupidly copied DG’s designs down to the last detail, including duplicating mistakes that were on the circuit boards.

32-bits Or Else

Ed wanted to do something in North Carolina. He wanted to send a message to The Commonwealth of Massachusetts and our governor Mike Dukakis that the state’s attitude towards business sucked. It was decided to move super secret FHP there. After we secured a building I began bi-weekly trips to Research Triangle Park near Raleigh. A pretty neat place, with the town of Chapel Hill nearby. Except for being away from family I liked going down there.

I got to meet the famous Fred Brooks who taught at the nearby University of North Carolina. I set up a meeting to find out if he would look in to FHP to help sort things out. He had about 20 little clocks in his office — alarm clock size. He was constantly punching them, stopping one and starting another. “Fred, what are you doing with all these clock?” Turns out he had become a fanatic regarding time management. He wanted to spend his time in the most efficient manner, and at the end of each week he would look at the clocks and figure out how much time he spent on various thought processes and activities.

My meeting with Fred was just a year after he had published “The Mythical Man-Month,” a book about his experiences as project manager of OS 360, the operating system for IBM’s iconic 360 line of computers. This was a hopelessly complex software project that included hundreds of programmers spread around the world. Fred had some great one-liners, like “adding manpower to a late software project only makes it later.” Maybe he figured that by managing his time more carefully he would avoid repeating the mistakes of IBM’s largest ever software project. In any case, after a brief description of FHP Fred said “No thanks. Not the slightest bit of interest. And Bill, good luck with that one….”

About a year after the move to North Carolina Ed put me in charge of all of FHP — the software and the hardware. I now owned the whole enchilada! Carl Carman, my counterpart on the hardware side, was happy, even eager, to rid himself of any connection to the project. FHP was still going nowhere and was hopelessly complex. My excuse for still holding back and not working harder to kill it was that Ed had promoted me to VP. Looks like I was willing to do anything to get that that title, including run a project that I didn't think had a chance of seeing the light of day.

Many smart engineers at headquarters saw what I saw — the odds of FHP ever getting finished were close to zero. DG desperately needed a 32-bit computer, and all the eggs were in the FHP basket. Until Tom West woke up. Tom, the guy that my freaks beaned with a frisbee, was one of the sharpest people in the company. He and Steve Wallach, another extremely smart guy, decided to do a 32-bit Eclipse. In other words, lower the risk of getting to 32-bits by leveraging off the existing product line.

A writer named Tracy Kidder wrote a pretty good book about this project — it won a Pulitzer Prize. Tom West did the hardware part and my guys in Massachusetts did the software. As is always the case, the software was the hardest part. Morphing a 16-bit operating system and it’s programming languages over to 32-bits is very complex.

Now there were competing projects to get to 32-bits — the relatively low risk Eagle (code name for the 32-bit Eclipse) and FHP, the pipe dream. Kidder’s book (Soul of A New Machine) did a reasonable job of describing the process, but he got a couple of things wrong. He didn’t give Tom and Steve and the project team nearly enough credit for saving DG’s buttocks. Eagle was an underground project. It was done in spite of management — it did not start as a sanctioned project. If Tom and Steve hadn’t done Eagle DG would have been screwed royally. Also, Kidder didn’t really mention how unusual DG was as a company. He talked a little about the weirdness, but the reader might have thought all computer companies were like DG. No way, it was in a class by itself.

DG had a really clever and aggressive PR machine. They were brash, in your face, cocky. At the trade shows DG posters were everywhere. Gimmicks like the microchip in the bellybutton got a lot of free publicity. When my guys came out with a new Fortran compiler PR came up with an unusual way of touting it. This compiler produced really good code — very efficient. But in churning out the machine instructions our Fortran compiler was very slow. It was a real pig. So, our PR guys came up with a full page ad with a pig right in your face. You couldn’t scan through Computerworld without stopping and reading ad. They did a lot of similar things — ad’s that you just couldn't ignore.

The best ad that DG unfortunately never ran had to do with Big Blue. In 1977 IBM finally decided to get into the minicomputer business with the Series/1. This market was growing too fast for them to ignore any longer. Our PR guys came up with a great full-page ad that was supposed to run in the Wall Street Journal:

SOME SAY IBM’S ENTRY LEGITIMIZES THE

MINICOMPUTER INDUSTRY

THE BASTARDS SAY WELCOME!

Data General

It was perfect!! Really characterized Data General — the bastards, no fear. But sadly it was never run. I suppose it was Ed that pulled the plug on it. Too bad, the ad would have generated all kinds of additional free publicity.

Tandem: Killing Me Softly

By the spring of 1978 I was in a real funk. I loved my job but I was restless. Tandem was riding high — they were the talk of the computing world. I was totally jealous of my old friends. These guys were now rich and famous!! If I had tried harder in 1974 I could have been a founder of Tandem!! I screwed up royally!!

Ok, so what do I do? Start a computer company?? Is that even possible? Well, my friends showed me that it was — I was as good as the Tandem guys and look what they had achieved! And look at DG — a highly successful company run by some smart guys with quirky ideas that broke all the rules. Really, if the DG and Tandem folks could do it, why not me?

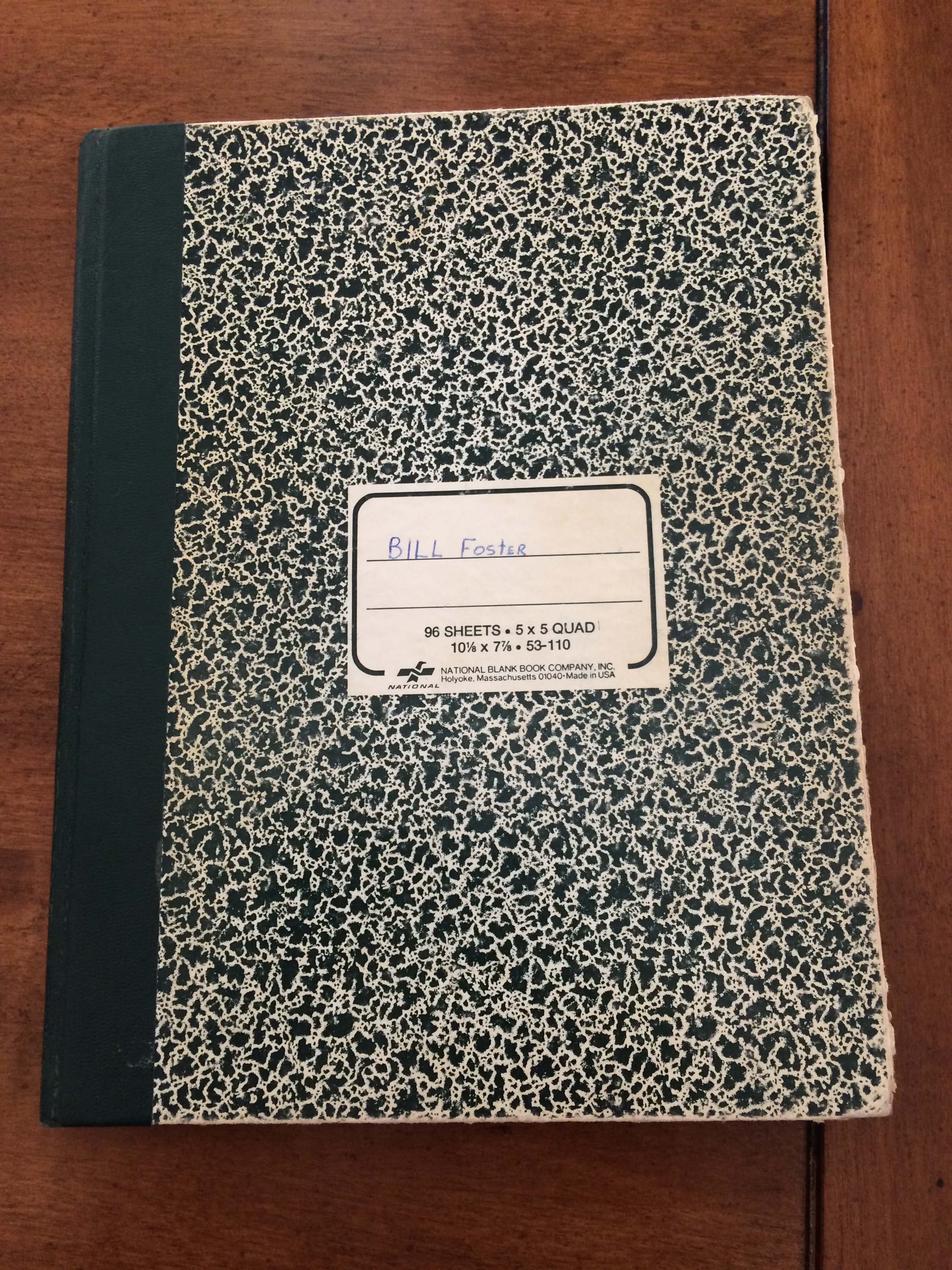

I am a note taker. And a note saver. I still have notes from staff meetings at HP in 1972!! The notes for “Nimbus” begin in March of 1978. (For some reason even back then I glommed on to the idea of naming my company after a type of cloud.)

I would need money, and an idea. The idea department was pretty empty back then. I would start a company to go after DEC, HP, DG, Prime, and Tandem. It would be a “low cost, 32-bit, virtual memory machine with a fast commercial instruction set.” Pretty weak. Nothing really new. No breakthroughs. So, most of the notes focus on staffing, schedules, and financing.

I knew this whole idea was pretty lame from the get-go. But by June of ’78 my focus began to change. I would go after Tandem. Strictly Tandem and the market they created — “non-stop” computers. The only improvements over Tandem that I could come up with were: “less application work to provide non-stop”, and “repair the system on the fly.” Plus, I now was a considering a 48 bit word. But none of that was very exciting. There still wasn’t the Technical Contribution -- the big idea that Dave Packard constantly preached about.

On the money side I got a list of the current venture capital companies, both East and West coast. And I figured that some of my University of Santa Clara business school professors might have an idea for funding — I was going to look them up.

In June of 1978 I flew my beat-up ten year old Cessna down to New Jersey to attend the National Computer Conference in New York City. I went right to the Tandem booth and got a nice demo from Dennis McEvoy. Their operating system was basically HP’s MPE, their language was HP’s SPL. I knew that stuff inside and out. This was the first time I touched their hardware -- the computer looked like a tank. Very rugged.

DG was doing nothing about this new market even though Tandem was getting all the headlines and a lot of new business. As far as I could tell HP, IBM, DEC, and all the others weren’t doing anything either.

This was back in the days before apps. You didn’t download free or nearly free stuff from the app store. Back then the customer wrote his own application software, or hired someone to do it. These applications only ran on one type of a computer. A DEC app would not run on DG or HP, etc. One of the first to break this rule was Gene Amdahl. His company made clones of the IBM 360 — his machines could run IBM software. Naturally IBM hated this and did all they could to make Amdahl’s life a living hell.

I figured that for DG or anyone else to go after Tandem they would have to come up with a product that was incompatible with their current line. The customer base would hate that and maybe jump ship — particularly DG’s customers who didn’t have a strong amount of loyalty. So it was unlikely that Tandem’s first threat would come from an older company. (I was wrong about this. It turned out there was a way to make a non-stop computer that was ran old software. But I hadn’t figured that out yet.)

We had a great family vacation planned for the summer of ’78. We went to a little island in the Bahamas — Harbor Island. Two weeks. I was determined to spend much of that time thinking. My real problem, the thing that was ultimately holding me back, was Dave Packard. His big booming voice constantly rattled around in my tiny brain: “YOU MUST MAKE A TECHNICAL CONTRIBUTION!!”

Oh crap, really? Can’t I just try to improve on Tandem? Isn’t 32-bits or maybe 48 enough?

“NO!! IF YOU DON’T COME UP WITH SOMETHING REALLY DIFFERENT YOU WILL FAIL!!!”

Double crap. What can I do that is new and different and better?

For two weeks, whenever I wasn’t playing with the family or doing other fun stuff, I thought, churned, mulled. When the vacation was over I had nothing. Nada. Zip-zero. Big time depression set in. It wasn’t going to happen. Not in this lifetime. I was never going to start company. Tandem would continue to prosper and I would be stuck in this place, in charge of a project that was going to fail. I gave up.

Nothing much exciting happened until the following summer. FHP continued to go nowhere, but surprisingly no one seemed to care. Ed never put pressure on me — never said “Foster, get that thing on track or you’re fired!” I’m really surprised he never leaned on me hard. By the time I left DG the project was at least 4 years old -- I'm not sure exactly when it started. Even at friendly old HP something would have happened by then. At minimum the project manager would have been replaced, or the entire thing would have been canceled. At DG nothing. Nada. Just keep pouring good money down a rat hole. I have no idea when they finally pulled the plug on FHP -- I was long gone.

Eagle, the 32-bit Eclipse, was making good progress. My software team did some amazing things to morph the old 16-bit software into something that would work. Tom West and his boys were strutting around, naturally happy that they were saving DG’s butt. Every time FHP missed another milestone West strutted a little higher.

Getting David Packard’s Monkey Of My Back

In June of ’79 I decided to try once again. Try for an idea. I need something, anything…. Ok, Tandem is the only fault tolerant company. They have a good product, but what is wrong with it? What don’t people like about Tandem? Maybe that’s how to attack the problem.

The most obvious problem was that their systems were hard to program. Basically, a Tandem system consisted of two or more computers connected together with a high speed bus. To achieve reliability the computers would “checkpoint” each other now and then. Computer A would work on a problem for a while, then when instructed by the application program it would send information over to Computer B. Likewise, B would send it’s stuff to A now and then. That way if either computer failed the other would always know what it’s partner had been doing, and carry on.

It was a good idea. But it was complex. Their operating system, the morphed MPE taken from HP, needed extensive modifications to make checkpointing work. But the worst thing was that the customer’s application had to actually perform the checkpointing commands — the app had to be designed for a feature that only existed on Tandem. These commands had really friendly sounding names, such as CHECKOPEN, CHECKMONITOR, CHECKSWITCH, GETSYNCHINFO, etc, etc. It was a royal pain for a programmer to work all of those commands into the application. And it meant that you couldn’t take an app from an IBM 360 or some other machine and move it over — it had to be extensively modified, or worse, rewritten.

I knew the trends. Software was becoming a problem. Software budgets were getting large. Businesses were beginning to spend more on software than hardware. A paradigm shift was happening. Historically the cost of hardware had far outweighed software. If I could come up with a scheme (“gimmick” as my friend John Couch would later call it) that eliminated all that extra software — well, that would be a breakthrough.

But how could you make a non-stop computer look like a normal one? Ok!! How about two computers?? Two computers running the same program??? After all, the cost of logic, the jelly beans that computers are made of, was dropping very fast. Why not just have two computers work on the same problem at once? It sounded wasteful, but it made things so simple. Maybe this is the beginning of an idea…..

The principle of doing non-stop in hardware, which on the surface seems pretty obvious, was the basis for my Big Idea. Tandem did their’s with software — my scheme would use hardware. It was just a glimmer of an idea and needed a lot of work. But it was a start. This very simple but major difference finally got Dave Packard off my back. Free at last!!!

Ideas were coming fast and furious. I figured I better start writing things down. I had a composition notebook that was always with me at DG as I went to meetings and such. It was small and easy to carry around. It allowed me to keep a record — so I that could look back and see how badly we were missing schedules, etc. So, for the dream company I called "Nimbus" I simply flipped this book upside down and backwards and starting writing on the back side of the pages. The front side was Data General. The back side was Nimbus. DG, Nimbus. Old world, new world. Old shit, new shit. Boredom, excitement. It was easy to flip from one world to the next.

This was actually a pretty dumb move considering that I worked for The Bastards, the toughest computer company ever. If my notes were ever discovered they would string me up. People would come to work one morning and there would be Bill, hanging by his neck on the flag pole, between Old Glory and the North Carolina state flag.

But never mind. I’m a risk taker. I ride motorcycles and fly airplanes. As a teenager I climbed Half Dome and sat on the ledge at the top with my legs dangling over, 3000 feet straight down. Dumb. And later that summer my buddies and I climbed the Golden Gate Bridge, from the base of the tower on up. Really, really dumb!! If I could do that dumb stuff then I could take the risk of walking around DG with these notes.

On the way to work each morning for the next two weeks I began pulling over at a secluded spot in the town of Ashland — home of the electric clock. (There are many iconic places where historic things happened in good old New England.) I found a spot deep in the woods where I could park and no one would see me. All the ideas that had come to me in the middle of the night I wrote down before I lost them.

I’m glad that I kept that notebook. It is extremely revealing — my very early thoughts about something that would eventually become Stratus. The first entry was June 10, 1979. The last was on June 24. The most productive two weeks of my business life! The first entry was a list 20 or so people that I would try to recruit as partners. All from HP — I was going back to California.

The list included Bob Miyakusu, John Welch, Len Shar, Gary Smith, John Sell, John Couch, Phil Sakakihara, Terry Opdendyk, and a few others. All really great guys, people who I liked and respected immensely. I would look them up as soon as I traveled west. Little did I know then that only a few would have any interest. By the summer of 1979 most of the best engineers had moved on — had left HP for Tandem or Apple or some other Silicon Valley startup.

On the next morning, on June 11, I pulled over to my spot in Ashland and wrote down in my little notebook the advantages of having two computers work on the same problem simultaneously:

1. No application impact!!!

2. Takes advantage of the most rapidly decreasing components: memory, logic!

3. Simplicity.

4. Can make use of software not designed for fault tolerance!!

This last point was somewhat groundbreaking. Doing non-stop with hardware solved one huge problem that prevented current companies from going after Tandem: backwards compatibility. If done right, you could strap any two machines together — DEC, or HP, or (gulp) Data General. But they would look like one computer to the software! The non-stop offering would be totally compatible with the old product lines. Customers would not revolt!

For the next 12 days I worked on refining this concept. Improving it. Asking questions, such as how often do I compare the two computers? Every minute or so? Every few instructions? Every instruction? I wrote down “run them in lockstep” but since I was not a hardware guy I didn’t know how to do this, or even if it was possible. I even considered strapping a couple of IBM System 38’s together. This way Nimbus wouldn’t have to invent a bunch of new hardware or software.

The other big question was: how do you know when a computer fails? What if it doesn’t just crash? What if it keeps running but just produces the wrong answer? What if one says 2 plus 3 equals 5 and the other says it equals 6?? Who do you believe?? Well, how about a third computer to break the tie?

The concept of three computers voting was not new — it had been written about in various publications for years. The idea was simple: have three computers work on the same problem, then vote on the answer. If there’s a disagreement majority wins. I had remembered a mention of voting in the Journal of the ACM. (Association for Computing Machinery, a geek organization I have belonged to for almost 50 years!) I looked through some old issues and sure enough, there it was! The ACM referenced an IBM article going back to 1962 that described voting. They mentioned that the famous Hungarian mathematician John Von Neumann had describe it a couple of decades earlier. I was also aware of a Silicon Valley startup called Magnuson that attempted a voting product but failed. So this was all public domain stuff — I was just re-hashing a very old concept.

I continued to toy with the idea, and started to figure out how many people this would take. I had ten people for software, 6 for hardware, and 3 for documentation. I would need 19 people for the first machine.

Notebook entry for June 21, 1979. Idea # 7. “Get Fortran, PL/1 from Freiburghouse.”

That would be Bob Freiburghouse, proprietor of his own small software company, Translation Systems. At DG we licensed Bob’s PL/1 complier — that’s how I knew him. This seemingly minor entry, almost a footnote, proved to be huge. Throw out everything else in my notebook except do it in hardware and talk to Bob. 99% of the value of what I had done so far was in those two decisions.

My last entry was June 24, just two weeks after I started taking notes. I had finally settled on voting — that was the way to go. Still, it seemed really expensive — maybe fault tolerance should just be an option? Maybe the customer could buy the extra processors only if non-stop was really, really important.

Looking back, I was wrong about voting. Hardware was still too expensive in 1979 to justify three conventional computers working on the same problem, except perhaps for a very tiny and uninteresting market. My Big Idea would have failed. But well after I left DG a technology breakthrough occurred — a powerful computer-on-a-chip became available from Motorola. This made the voting viable.

I did have one annoying little note on this last page: “no redundancy” with an arrow pointing to the voter. This plan had one big flaw: what if the voter fails? The voter was an obvious weak link. The whole idea of a non-stop computer is that no single component failure could bring the entire system down. How about two voters? But what if the voters disagree — who do you believe? IBM had a solution in their 1962 paper but it was hopelessly complex and extremely expensive. Ever see the cartoon of the mad scientist at the blackboard? A very complex equation, and he is asked to explain the little note in the middle: “And then a miracle occurs.” That was my thought — don’t worry about it now, somehow a miracle will occur.

Finally I was excited about something. But wait! I’ve got that DG employment agreement — every synapse in my brain belongs to them — or at least that was their claim. I knew there was no invention here — that Data General could never claim they owned the idea. But the only way to move ahead with a clear conscience was to quit and strike out on my own. I decided to put everything on hold until I was free and clear of DG. Hmm… Three small kids. Limited resources. No outside source of income. Maybe I should slow down, think about this for a little bit. One thing for sure — no more work on Nimbus. Once again, everything ground to a halt. Chicken.

A few days later I was sent to Europe to talk to our people about 32-bits and what we were doing about it. Everyone knew we were late to the market and employees were becoming concerned, so it was decided that we should open up a little about our plans. In the middle of my first night in England I suddenly popped awake. There was a voice in my head. “Just do it. Go home, quit DG, and just try, for crying out loud! You have the beginnings of an idea. You’re excited about it. JUST DO IT!!!”

An ugly little red devil had appeared on my shoulder. “COWARD. DO IT!!”

And then an angel popped up on the other side. “It’s too risky. You have a wife and three little kids to worry about. How could you think of leaving a great job?” (sob, sob)

“OH SHUT UP!! HE’S GOT NOTHING TO LOSE. THE WORST THING THAT HAPPENS IS HE FAILS! SO WHAT? JUST DO IT, CHICKEN!!”

The devil won out. I waited for morning to arrive in Boston and called Marian. When I told her I was going to quit start a computer company she said “Ok, whatever, see you later.” She wasn’t too excited — she had heard this from me before, with no action.

Everything happened quickly after that. I got home, typed up my resignation letter. Marian asked how long we could live on our savings. About a year. “Ok, I’ll keep track of the cash and when we’re a month away from being broke I’ll tell you to get a job.” No complaints — just the facts. Marian was and is a bottom line person. “The bottom line is: when we’re almost broke you go get a job. Up until then I am totally with you.” Great! We’re about to spend our life savings, all the money we had for the kid’s college fund — and she never complained. Total support from day one! Could you imagine how impossible this would have been if she had said, “OMG we have three small kids and you’re going to waste our life savings! How could you consider doing this?!!”

Next morning I walked into Ed’s office. “Ed, I’m resigning — here’s my letter giving two weeks notice.”

“Why?”

“I’m going to start a computer company.”

“Where?”

“Back home. The West Coast. I’m going back to California.”

“All right.”

That was it. He was friendly, almost supportive. He didn't kick me out like Hewlett Packard had done!! Herb was right -- DG is fair!!!

Electronic News 9/3/79

I went back to my office and sat. I didn’t tell anybody. I figured Ed would. A week went by. Nothing. Ten days, nothing. Nobody seemed to know. It was business as usual. On my final day I waited for Ed to arrive and asked what the plan was. “Steve Gaal is replacing you. Good luck.” Steve was a really good guy — this was a great choice. But more importantly, Ed wished me good luck!! Fantastic! Maybe he’ll leave me alone…

Well, he didn’t. The first lawsuit threat came just a few months later. The second was just after we closed our initial financing. The final threat came in 1981.

Call Me Flounder

I was totally down in the dumps in the fall of ’79. It had been three months since I left DG and everything was going wrong. I had bombed in California. I had no partners. I was a total failure at raising money — none of the venture people said no, but nobody said yes. They were stringing me along and Marian and I were closely watching our remaining cash. I avoided everyone — friends, family. I didn’t want people knowing how bad things were.

Fred Adler was the initial investor in Data General. He was responsible for raising $800k in two segments — that’s all they needed to get to a public offering. I had met Fred a few times while working for Ed. Apparently he was keeping tabs on my failing effort. I got a call out of the blue. “Bill, I understand you’re having trouble raising money. Send me a copy of your business plan and if it looks good I might invest.”

Once again the ugly devil popped up on my shoulder. “Don’t do it!!! He can’t be trusted!!”

The cute little angel appeared on the other side and meekly said, “But you’re not getting anywhere. You’re eating through all of your savings. What about your poor little wife and kids?” (sob, sob)

“It doesn’t matter. DON’T DO IT!!!!”

I tend trust people. That’s where I start. But sometimes it backfires. Remember that classic scene in Animal House when the frat-brats trashed Flounder’s car? “Flounder, don't look so depressed. You f...ed up. YOU TRUSTED US!!!” Just call me Flounder. I knew it was dangerous to send Adler my plan, but I was desperate. The angel won out. I mailed my plan off to his office in New York. I screwed up.

Several weeks later I was chopping wood in our back yard. We had a ton of oak trees and my plan was save some cash and heat our house that winter with wood. Our daughter Robin called out, “Dad, phone call. His name is Mr. Kaplan.” Wow! Carl Kaplan. One of Adler’s lawyers. I had met him a few times in New York and liked him — he seemed like a really good guy, a real straight arrow. My heart jumped. This might be it!! They’re going to invest! My dream might actually come true!

It didn’t take long for my hopes to be crushed.

“Hi Carl, how’s it going?”

He got right to the point. “Bill, thanks for the business plan. Looks like a great idea. But don’t get too excited. We’re going to sue you.”

“WHAT!!!!”

“We’re going to sue you for Breach of Fiduciary Responsibility.”

Wow! Talk about going from a high to a low in about a nanosecond!! I was totally bummed.

“What in the hell is this fiduciary crap?”

“We’re going to say that you’re supporting yourself by selling names of employees to headhunters. You’re selling inside information.”

“But it’s a lie — total bullshit. And it’s absurd — no one will believe you.”

“That doesn't matter. Just suing you will scare off all the venture guys. So give it up — unless you want a lawsuit on your hands. You’re never going to get any money.”

After Kaplan hung up big time depression set in. I figured this was just about the worst day in my life. But as happens often, it was a turning point. For the positive. The shackles were off. I had nothing to lose. This threat gave me the freedom to move ahead.

These guys really screwed up! They had my plan and did nothing with it except threaten me. They had the plan for a company to go after Tandem — the hottest and most exciting computer company in 1979. They had a chance to invest and make a lot of money but instead they chose to intimidate.

The next threat came on May 12, 1980 one week to the day after we put $1.7 million in the bank. (I know the exact date from my trusty notebook.) Our lead investor Joe Gal got a call from Fred Adler informing him that once again they were about to sue. We had only enjoyed our newfound fortune for one measly week and DG was threatening me for a second time!! Joe suggested I call Ed to try to work something out. On May 14 I called Ed. He was cordial but insisted that as an ex-officer of DG I was using proprietary information — the names of employees. At that time we had hired only 4 people from his company. I told Ed I didn’t know any of them — Gardner Hendrie had come up with the names. He should sue Gardner. (Sorry for throwing you under the bus, Gardner….)

I then said that we had made offers to 2 or 3 others and I didn’t know yet if they had accepted, but after them we would stop, for a year. Ed agreed that for one year he would back off. Then he mentioned that Adler had been wanting to sue me for months, but Ed had held him back. I believed him. I never thought throwing around lawsuits was in Ed’s DNA. He could achieve all the success he wanted just by using his brain.

The final threat came one year later, again for hiring just a couple of their people. From that point on they left us alone. While Ed never did sue me or Stratus, it was unfortunate that all of this nonsense did prevent a bunch of good people from joining us. These folks would have been in on the ground floor of an exciting startup but were held back by their employer.

In 1981 Harvard wrote a case study about Stratus — the trials and tribulations of a would-be entrepreneur who didn’t have a clue about how to raise money. I lied to the case writer — told him that I had no clue about who I was going to compete with until after I left DG. I was still afraid of them, even in 1981. For the next 10 years when the case was taught at Harvard and later at Stanford I would start by explaining to the class that in fact I was not totally brain-dead — I had decided before leaving my job that I was going after Tandem.

When my father died years ago I was going through his things and found a letter from me that he had saved. It was dated May 30, 1980 — three weeks after we got our first round of money. I had no idea yet whether or not we would ever be successful. Here’s a quote: “There is still a chance that DG will sue us. They know they can’t win. Their objective would be to make life difficult for us by wasting time and money with lawyers. It’s a ridiculous way to run a company, and in the long run I think their policies will backfire on them.”

Did their policies backfire? You bet they did! Before the first threat I had no intention of going after Data General people. In fact, I was doing all I could to stay away from them. I tried getting something going in California — as far away from DG as possible. When that failed I had no choice but to stay in New England. Still I avoided DG people. The company scared me. I would have to find engineers from DEC or Prime, but there was one giant problem: Other than my neighbor who ran sales for Prime Computer I didn’t know a single soul at either company. I was pretty much at the end of my rope.

Then came the first threat — the ridiculous trumped-up charge that I was selling names to headhunters. Here I was, with no money and no partners. What were they afraid of? Why did they even bother with me? During the fall of 1979 when that threat came I was dead in the water.

Carl Kaplan’s call only inspired me. I had nothing to lose!! The gloves were off! We still had six months of cash left — I wasn’t close to giving up. I eventually called Gardner Hendrie, one of DG’s best hardware people. And as they say, “the rest is history”. Gardner became a co-founder and was a critical link in our eventual success. We got our first round of financing because of his contacts. And, most importantly, he and his team came up with a fantastically elegant but simple solution to the non-stop voter problem. If Adler had just left well enough alone I never would have gone after Gardner, and Stratus never would have happened.

My three years at DG were life-changing. The move east got me out of HP and taught me about the real world. In doing so I joined one of the most unusual companies ever. I learned a lot and became tough(er). They made me a survivor. They forced me to think about profit and cash flow — things that were never emphasized at HP.

I valued the lessons from DG. I told myself that if I ever got a company going I would try to take the best from both HP and DG. HP’s attitude toward people — trust them, treat them with respect. Emphasize quality in everything. And do whatever it takes to keep customers happy.

And from DG it was their emphasis on profits and cash. Doing what it takes to survive. In a startup cash is king. The chance of survival is small. DG taught me to watch my bottom line.

Many of the original minicomputer companies are now a part of Hewlett Packard, partly because of HP’s own acquisitions and later from their merger with Compaq. What is left of Tandem is buried somewhere deep in the bowels of HP. DEC, the first minicomputer company, is deep within those same bowels. Data General was acquired by EMC which is about to be acquired by Dell. All the original minicomputer companies are gone -- except, that is, for Stratus, which still survives as an independent privately held company.

I’ve been asked what I think about Ed — the threats and the efforts to kill my venture. I’ve always liked Ed. I liked working for him. I like him as a person. We’ve enjoyed some good times together long after we both left Data General. He is a great guy and has done many good things for others. What about when I was being harassed? I wasn’t too fond of Ed then. But I can't imagine Stratus ever existing if Ed had not brought me to Massachusetts. How could I ever hold a grudge against him? After all, I'm describing things that happened nearly 4 decades ago! It was always just business with Ed —none of the threats were ever personal. He was taught somewhere that harassing now and then was the way to run a company. He was given some bad advice.